|

|

|

Chapter 8a

Barbarians at the Gate

(Isaiah 36-37)

We have been looking primarily at poetry thus far in the book of Isaiah. In this section we will look at material that includes the longest prose section in the book. We'll be looking at the Assyrian siege of the city of Jerusalem in chapters 36 and 37.

The year was 701 B.C. It had finally come down to this. There were no other options. There were no alternatives. There were no more backup plans. There was no escape. The representative of the emperor of the mightiest kingdom that the world had ever known was sitting astride his horse at the gate of Jerusalem demanding that the city surrender. Surrender or die. If the city acquiesced to his demand, then the inhabitants would live; but they would be subjected to the whims of their new Assyrian overlord. Even more, they would be subjected to those of a different value system--an evil value system; a different worldview--one without God. They would have to give up their religion and adopt the religion of the Assyrians. Do this and live. Don't do this and die. The choice was stark. No wiggle room. No ambiguity. The decision final.

The small kingdom of Judah was all alone. The Assyrian Empire was quickly expanding, destroying all kingdoms in its path. It soon would stretch from Cyprus in the West to near the Black Sea in the north to the Persian Gulf in the east. It would soon even conquer mighty Egypt in the south and expand its control far into the interior of the continent of Africa. There was only one small dot on the map that would keep it from being uniform in its coverage: the city of Jerusalem. Even all of the other fortified cities of Judah had fallen. Jerusalem was all alone against the greatest fighting force of all time. There was no hope of help from elsewhere. To not yield would mean death. To yield would mean not only the end of their freedom, but the end of their nation, their culture, and, yes, their religion.

The barbarians were at the gate, and they wanted an answer.

The origin of the phrase "barbarians at the gate" is obscure. It may have originated during the time of the Roman Empire, when the Visigoths, Huns, and Vandals were making inroads in the waning days of the Empire. Or it may have originated much later in the sixteenth or seventeenth century when Islamic forces were threatening the gates of Vienna, Austria.

In some ways the Assyrians were not barbarians as we use the term today. They had a long and proud history dating back prior to the 24th century B.C., at which time they were dominated by Sargon the Great, whom the Bible likely refers to under the name of Nimrod (or Nimrud) in Genesis chapter ten (Genesis 10:8-9; vid. I Chronicles 1:10; Micah 5:6). They were rich and powerful and fully capable of dominating lesser kingdoms around them.

But the Assyrians were barbarians in many ways. They were known as a very warlike and cruel people. After conquering a land, they did not do as the Persians did. The Persians tried to be, to some extent, friendly with and accommodating to their provinces and provide somewhat reasonable representatives of the Emperor throughout the Empire. They allowed local freedom in many things including religion. The Assyrians, on the other hand, weren't concerned with having friendly representatives of the Emperor in their provinces. They seemed to prefer instilling fear in their subjects rather than resorting to good government. They terrified their conquered subjects so much that any idea of rebellion wasn't given a second thought. They would cut off the heads of their victims, along with their arms and legs, and place the heads on spikes as a reminder. They would impale their enemies on poles. They would skin rebels alive and use their skins to decorate walls.

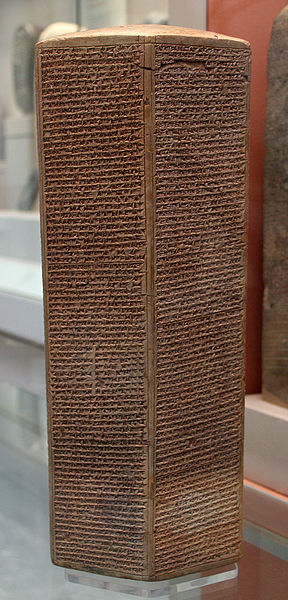

From the reign of the ninth century B.C. Assyrian ruler Ashurnasirpal II, we have the following:

...many soldiers I captured alive. From some I cut off their noses, their ears, and their fingers, of many I gouged out their eyes. I made one pile of the living (and) one of heads. I hung their heads on trees around the city. The male children and the female children I burnt in the flames. The city I destroyed, consumed, and burnt with fire. I annihilated it.

(Annals of Ashurnasirpal II)

I flayed as many nobles as had rebelled against me (and) draped their skins over the pile; some I spread out within the pile, some I erected on stakes upon the pile, (and) some I placed on stakes around about the pile. I flayed many right through my land (and) draped their skins over the walls.

(Ashurnasirpal II. "Ninurta Temple Inscription")

|

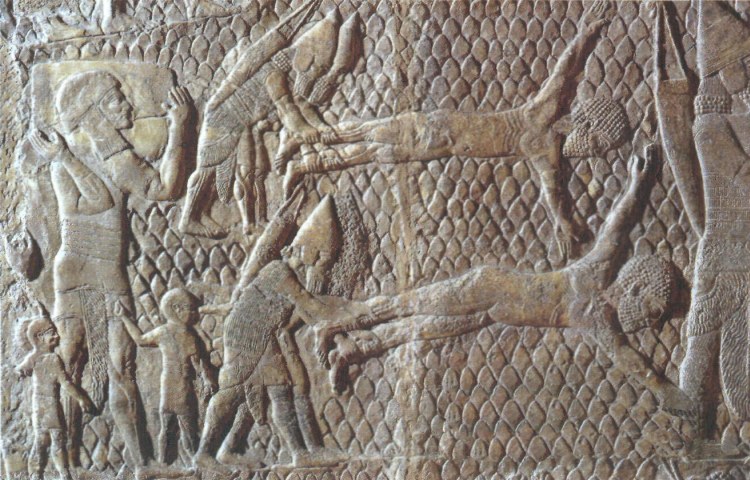

Assyrian Torture/Beheading/Impaling Scene

Assyrian Torture/Beheading/Impaling Scene

(Balawat Gates; British Museum)

(Public Domain)

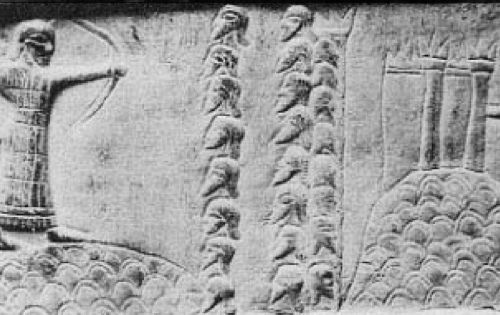

Heads of Conquered Victims on Stakes

(Balawat Gates; British Museum)

(Public Domain)

Pile of Heads from Beheaded Assyrian Enemies

(Relief from the Southwest Palace at Nineveh;

British Museum)

(Credit: Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin [cropped];

BY-SA 4.0 Creative Commons License)

|

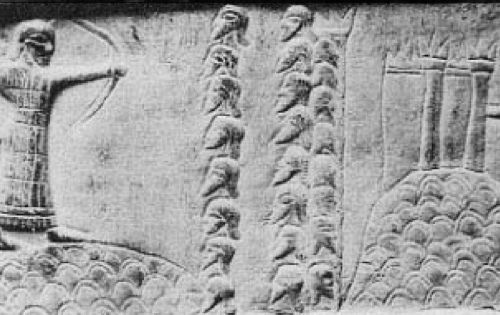

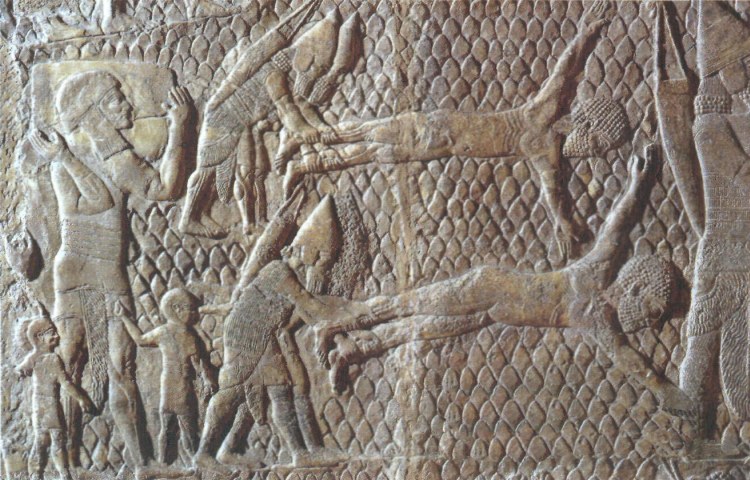

Assyrians Flaying Soldiers from Lachish

(Siege of Lachish Reliefs from the

Southwest Palace at Nineveh; British Museum)

(Credit: Arvasbao [Wikipedia]; Public Domain)

Assyrians Impaling Soldiers from Lachish

(Siege of Lachish Reliefs from the

Southwest Palace at Nineveh; British Museum)

(Public Domain)

|

The implication seems to have been, "Don't act up, or we'll be back." In this sense, the barbarians were definitely at the gate, but the barbarians also had a powerful and inventive culture to back up their military prowess.

Hezekiah sent for the prophet Isaiah for advice. Isaiah's answer was to not be afraid; that the king of Assyria would not conquer the city, and that he would return to his homeland.

So, was Hezekiah to depend on the word of one who claimed to be a prophet and who claimed to see visions? Was Hezekiah supposed to give an answer to the Assyrian emperor's envoy that would seem certainly to mean the destruction of the city and the death or captivity of its inhabitants? Was he to trust in the words of an ancient book that had been written by men claiming to speak for some old man in the sky? Was he to trust in the superstitions of a primitive tribal culture? Could a simple faith preserve him when even the advances of more modern weaponry could not prevail? The other gods of all the other cities in the path of the Assyrians had not preserved their adherents. What confidence could Hezekiah possibly have, in the face of the massive Assyrian forces arrayed against him, that this would turn out any differently?

Those in Jerusalem familiar with world events knew that the situation looked hopeless. Those who were tasked with speaking to the emperor's envoy urged him not to speak in the language of the people of Jerusalem, so as not to startle them. The envoy mocked those with whom he spoke by offering 2000 horses to them so as to perhaps make the battle a little more even. But even 2000 horses, a cavalry indeed, would not make a dent in the Assyrian forces arrayed against the city. Even fortified cities had not slowed the advance of the Assyrians. History records that the Assyrians were the inventors of the battering ram.

With this new weapon, they could simply go up to a previously impregnable city gate, or to a weak place in a city wall, and break through. And now they stood at the gate of Jerusalem ready to enter.

And the Rabshakeh said to them, "Say to Hezekiah, 'Thus says the great king, the king of Assyria: On what do you rest this trust of yours?

Do you think that mere words are strategy and power for war? In whom do you now trust, that you have rebelled against me? Behold, you are trusting in

Egypt, that broken reed of a staff, which will pierce the hand of any man who leans on it. Such is Pharaoh king of Egypt to all who trust in him.

But if you say to me, "We trust in the LORD our God," is it not he whose high places and altars Hezekiah has removed, saying to Judah and to

Jerusalem, "You shall worship before this altar"?'"

(Isaiah 36:4-7)

The Assyrian Emperor's representative was under the false impression that, when Hezekiah removed the altars of the pagan idols from the high places, that he was removing the altars of Jehovah.

"'Come now, make a wager with my master the king of Assyria: I will give you two thousand horses, if you are able on your part to set riders on them.

How then can you repulse a single captain among the least of my master's servants, when you trust in Egypt for chariots and for horsemen?...

Beware lest Hezekiah mislead you by saying, "The LORD will deliver us." Has any of the gods of the nations delivered his land out of the hand of the king

of Assyria? Where are the gods of Hamath and Arpad? Where are the gods of Sepharvaim? Have they delivered Samaria out of my hand? Who among all the gods

of these lands have delivered their lands out of my hand, that the LORD should deliver Jerusalem out of my hand?'"

(Isaiah 36:8-9,18-20)

The expansion of the Assyrian Empire had been relentless, and everything had fallen in its path: Susa in Persia; Ur in lower Mesopotamia; cities in the far north near the Black Sea; Kanish and nearby cities in Asia Minor; the island of Cyprus in the Mediterranean; Damascus, the formidable capital of Syria that had oppressed Judah; the coastal trading cities of Arvad, Byblos, Sidon, and even mighty Tyre; the capital city Samaria of the northern Kingdom, once glorious, now destroyed, no longer in existence, its kingdom forever gone; Sela, the heart of the Edomite kingdom; even to Dumah in the northern reaches of the Arabian desert; and even further to the Sinai peninsula; and, yes, it would soon extend even to the mighty, legendary, land of Egypt, where cities of renown like Tanis, On, and Memphis would fall one after another; even further south in Upper Egypt cities like Abydos and even mighty Thebes would not escape; and the conquest would continue even further into the heart of the African continent toward the little known interior.

Only one dot on the map would remain: lowly, weak Jerusalem. How could it stand? How could it possibly stand?

Given the utter and complete hopelessness of the situation, in which clear logic and self-interest obviously dictated only one choice--that of surrender, hasty and unconditional--Hezekiah did the unthinkable: He chose God.

As soon as King Hezekiah heard it, he tore his clothes and covered himself with sackcloth and went into the house of the LORD....

And Hezekiah prayed to the LORD: "O LORD of hosts, God of Israel, enthroned above the cherubim, you are the God, you alone, of all the kingdoms of the

earth; you have made heaven and earth. Incline your ear, O LORD, and hear; open your eyes, O LORD, and see; and hear all the words of Sennacherib,

which he has sent to mock the living God. Truly, O LORD, the kings of Assyria have laid waste all the nations and their lands, and have cast their gods

into the fire. For they were no gods, but the work of men's hands, wood and stone. Therefore they were destroyed. So now, O LORD our God, save us from

his hand, that all the kingdoms of the earth may know that you alone are the LORD."

(Isaiah 37:1,15-20)

It needs to be understood that, especially in a situation like this, that faith in and of itself cannot save. The kings and rulers of other nations and kingdoms also had faith--some perhaps even as great as or greater than that of Hezekiah. The difference was in the object of that faith. If there actually is no True God of All the Earth who is the Creator of the Entire Cosmos and Everything in It, then no amount of faith that there is such a God will protect you. The rulers of surrounding cities and kingdoms placed a strong, heartfelt faith in their so-called gods, hoping for and expecting their protection. But those gods were merely figments of their imagination, vapors of their minds, nonexistent, powerless, empty boxes in an empty room.

Faith, in and of itself, cannot save from an advancing Assyrian army.

But, if among the stories of the ancients, there is a light of uninvented reality; if among the lies and myths of the ages, there is a genuine thread of certainty; if among the multitudes of falsehoods about demigods and goddesses, there is indeed a God who rules over all, then simple faith may become endless power.

And the angel of the LORD went out and struck down 185,000 in the camp of the Assyrians. And when people arose early in the morning, behold, these were

all dead bodies. Then Sennacherib king of Assyria departed and returned home and lived at Nineveh. And as he was worshiping in the house of Nisroch his god,

Adrammelech and Sharezer, his sons, struck him down with the sword. And after they escaped into the land of Ararat, Esarhaddon his son reigned in his place.

(Isaiah 37:36-38)

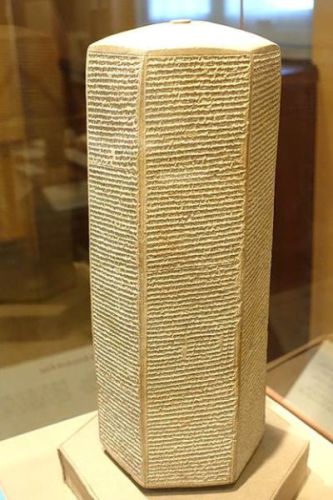

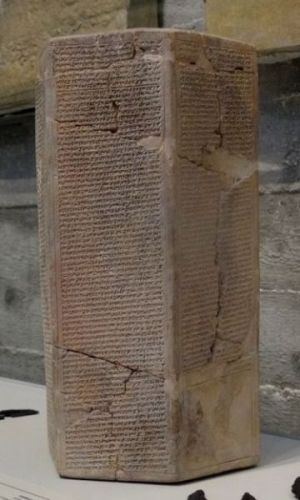

The military exploits of Sennacherib are recorded in Sennacherib's annals, which are found in almost complete form in three ancient clay prisms: the Taylor Prism (in the British Museum in London), the Oriental Institute Prism (in the Oriental Institute of Chicago), and the Jerusalem Prism (in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem). (There are also some additional fragmentary remains in existence.)

It is characteristic of ancient official inscriptions that they would give overwhelmingly glowing depictions of ancient rulers and their accomplishments in a way that was so "over the top" that it might embarrass even our public officials today. For example, from the "Standard Inscription of Ashurnasirpal II", a ninth century B.C. Assyrian Emperor:

Palace of Ashurnasirpal, priest of Ashur, favourite of Enlil and Ninurta, beloved of Anu and Dagan, the weapon of the great gods, the mighty king, king of the world, king of Assyria; son of Tukulti-Ninurta, the great king, the mighty king, king of the world, king of Assyria, the son of Adad-nirari, the great king, the mighty king, king of Assyria; the valiant man, who acts with the support of Ashur, his lord and has no equal among the princes of the four quarters of the world; the wonderful shepherd who is not afraid of battle; the great flood which none can oppose; the king who makes those who are not subject to him submissive; who has subjugated all mankind; the mighty warrior who treads on the necks of his enemies, tramples down all foes, and shatters the forces of the proud; the king who acts with the support of the great gods, and whose hand has conquered all lands, who has subjugated all the mountains and received their tribute, taking hostages and establishing his power over all countries.

(from the "Standard Inscription of Ashurnasirpal II")

Sennacherib, a late eighth/early seventh century emperor, and the emperor at the time of the siege of Jerusalem described by Isaiah, likewise brags about himself:

Sennacherib, the great king, the mighty king, king of the world, king of Assyria, king of the four quarters, the wise shepherd, favorite of the great gods, guardian of right, lover of justice, who lends support, who comes to the aid of the destitute, who performs pious acts, perfect hero, mighty man, first among all princes, the powerful one who consumes the insubmissive, who strikes the wicked with the thunderbolt; the god Assur, the great mountain, an unrivaled kinship has entrusted to me, and above all those who dwell in palaces, has made powerful my weapons; from the upper sea of the setting sun to the lower sea of the rising sun...

(Sennacherib's Annals)

He then goes on to brag at length about all of his conquests. But, in amongst all of his bragging, something had to be said about Jerusalem.

As for Hezekiah the Judahite, who did not submit to my yoke: forty-six of his strong, walled cities, as well as the small towns in their area, which were without number, by levelling with battering-rams and by bringing up seige-engines, and by attacking and storming on foot, by mines, tunnels, and breeches, I besieged and took them. 200,150 people, great and small, male and female, horses, mules, asses, camels, cattle and sheep without number, I brought away from them and counted as spoil. (Hezekiah) himself, like a caged bird I shut up in Jerusalem, his royal city....His cities, which I had despoiled, I cut off from his land....As for Hezekiah, the terrifying splendor of my majesty overcame him...

(Sennacherib's Annals)

Notice that in all of his bragging there is one thing that he doesn't say. He doesn't say that he conquered Jerusalem. He couldn't say that, because he didn't.

Hezekiah...himself, like a caged bird I shut up in Jerusalem, his royal city.

The glorious official records could not say that there was still a small, weak, unconquered town in the very heart of the Empire. So the official records put the best spin on it that they could. But even the Assyrian sources implicitly concede that Jerusalem remained unconquered.

Isaiah had said that this is what would happen. When Hezekiah had previously gone to Isaiah for advice, Isaiah told him:

"Therefore thus says the LORD concerning the king of Assyria: He shall not come into this city or shoot an arrow there or come before it with a shield

or cast up a siege mound against it. By the way that he came, by the same he shall return, and he shall not come into this city, declares the LORD. For I

will defend this city to save it, for my own sake and for the sake of my servant David."

(Isaiah 37:33-35)

Other historical sources also seem to indicate that something very unusual happened that day outside the walls of Jerusalem.

Josephus cites the Babylonian historian Berosus (early third century B.C.), who was also a priest of the Babylonian god Marduk:

Berosus, who wrote of the affairs of Chaldea, makes mention of this king Sennacherib, and that he ruled over the Assyrians, and that he made an expedition against all Asia and Egypt; and says thus:

"Now when Sennacherib was returning from his Egyptian war to Jerusalem, he found his army under Rabshakeh his general in danger, for God had sent a pestilential distemper upon his army; and on the very first night of the siege, a hundred fourscore and five thousand, with their captains and generals, were destroyed. So the king was in a great dread and in a terrible agony at this calamity; and being in great fear for his whole army, he fled with the rest of his forces to his own kingdom, and to his city Nineveh; and when he had abode there a little while, he was treacherously assaulted, and died by the hands of his elder sons, Adrammelech and Seraser, and was slain in his own temple, which was called Araske. Now these sons of his were driven away on account of the murder of their father by the citizens, and went into Armenia, while Assarachoddas took the kingdom of Sennacherib."

(Flavius Josephus. Antiquities of the Jews. X.ii)

It seems that the Egyptians and Greeks were also aware that something unusual had happened. About the same time that Jerusalem was under siege, the Assyrian forces of Sennacherib were outside the walls of the Egyptian city of Pelusium. When the Assyrian army suddenly withdrew, according to the Greek historian Herodotus, the Egyptians tried to claim the unusual event for their deities, saying that one of their gods had during the night sent a "multitude of field mice" (or a "swarm of field mice") into the camp of the Assyrians, and the field mice had eaten the bowstrings off of their bows and the leather thong-handles off of their shields. When the Assyrians ran out of bows, they were forced to withdraw. One of the problems with claiming it for the Egyptian deity, though, is that the Assyrians eventually came back and conquered Egypt and beyond, but Jerusalem remained unconquered in the bosom of the Assyrian Empire.

Now concerning this Sennacherib, Herodotus also says, in the second book of his histories, how "this king came against the Egyptian king, who was the priest of Vulcan; and that as he was besieging Pelusium, he broke up the siege on the following occasion: This Egyptian priest prayed to God, and God heard his prayer, and sent a judgment upon the Arabian king." But in this Herodotus was mistaken, when he called this king not king of the Assyrians, but of the Arabians; for he saith that "a multitude of mice gnawed to pieces in one night both the bows and the rest of the armor of the Assyrians, and that it was on that account that the king, when he had no bows left, drew off his army from Pelusium."

(Flavius Josephus. Antiquities of the Jews. X.ii; cf. Herodotus. Histories. Book II.141)

Herodotus says that, when Sennacherib marched against Egypt, the Egyptian soldiers refused to go to battle against him. A priest of the Egyptian god Hephaestos, by the name of Sethos, then went into the temple of Hephaestos and cried to him about the impending danger. Supposedly Hephaestos then promised that he would send help. Herodotus then writes:

...not one of the warrior class followed him [i.e., Pethos], but shop-keepers and artisans and men of the market. Then after they came, there swarmed by night upon their enemies mice of the fields, and ate up their quivers and their bows, and moreover the handles of their shields, so that on the next day they fled, and being without defence of arms great numbers fell."

(Herodotus. Histories. Book II.141)

The reprieve for Pelusium and the rest of mighty Egypt was only temporary. The Assyrians returned and conquered both Lower Egypt and Upper Egypt. However, there would still remain the small, weak, and lowly city of Jerusalem within the very heart of the Assyrian Empire--a single tiny dot remaining unconquered within a vast empire encompassing almost all of the Middle East.

The Babylonian reference to a "pestilential distemper", and the Egyptian reference to a swarm of field mice sounds a lot like bubonic plague. But whatever the instrument that was used, history seems to record that something very unusual happened that day outside the walls of Jerusalem...something that could not be explained away by attributing it to "primitive superstitions". The God of All the Earth intervened in human affairs that day and gave a dramatic respite, a reprieve to his people that could not easily be explained away.

|

Assyrian Torture/Beheading/Impaling Scene

Assyrian Torture/Beheading/Impaling Scene

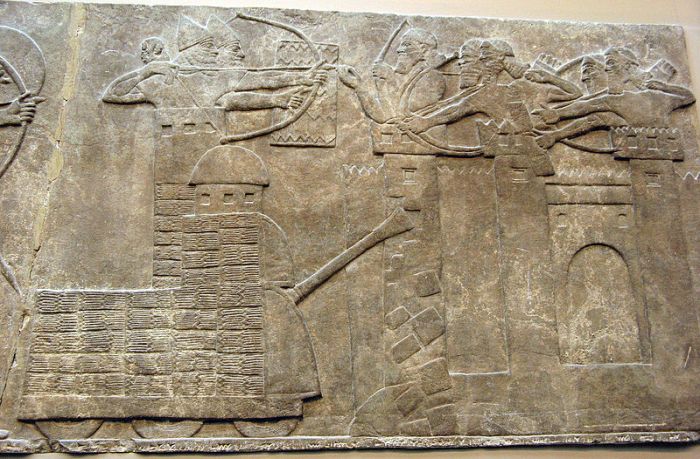

Assyrian Battering Ram

Assyrian Battering Ram